7 Trailblazing Women in History

Written by Nicole Smithee

Happy Women’s History Month! This month we’re celebrating the mothers, sisters, daughters, friends, teachers, coaches, leaders, neighbors, artists, athletes, believers, innovators, trailblazers, and advocates who have shaped our world and inspired across generations.

Below is a list of women who have undeniably changed the world for the better. Some names may sound familiar to you and others you may have never heard of. They are from different time periods, childhood experiences, and cultures. They all had unique gifts and passions. Though their differences are many, they all share one unifying trait—an overcoming spirit. These women dreamed of a better tomorrow, persevered against all odds, and fought to leave a legacy for generations to come. May their lives inspire you to dare greatly, love deeply, and make a difference in the world around you!

Junko Tabei, the first woman to summit Mount Everest and climb the Seven Summits

Junko Tabei. Image courtesy of Daily Hawker

Although Junko Tabei was the first woman to summit the world’s largest peak, she preferred to simply be known as the 36th person to climb Mount Everest. In mid-20th century Japan, Tabei fought against pervasive sexism and cultural expectations in order to become the first woman to climb the Seven Summits—the highest mountains in each of the seven continents of the world.

Tabei was born in Miharu, Fukushima in 1939 and fell in love with climbing on a school trip to Japan’s Mounts Asahi and Chausu when she was only ten years old. While attending Showa Women’s University, she began earnestly climbing. Often she was the only woman on climbing trips and in clubs. Some men refused to climb with her. She persisted, and in 1969 she founded a climbing club for women called the Joshi-Tohan Club (Women’s Mountaineering Club). In 1970, Tabei led her club on a successful climbing expedition to Annapurna III.

In the spring of 1975, Tabei then led her club to Mount Everest. At 9,000 feet, they were hit with an avalanche and Tabei was buried and knocked unconscious. Miraculously, her team was able to rescue her from the debris. After being unable to walk for the next two days, Tabei continued climbing alone and arrived at the top of the summit crawling on her hands and knees.

In 2002, Tabei returned to school to study ecology. She became an environmental advocate, and her research focused on the environmental degradation of Mount Everest. She served as the Director of the Himalayan Adventure Trust of Japan, a group seeking to protect fragile high-alpine environments from the traces left by hikers and climbers.

After a four year battle with cancer, Tabei passed away in 2016, at 77 years old. She left behind a legacy of extraordinary human achievement, environmental activism, and overcoming opposition for women to be welcomed into the climbing world.

“I can’t understand why men make all this fuss about Everest—it’s only a mountain.” –Junko Tabei

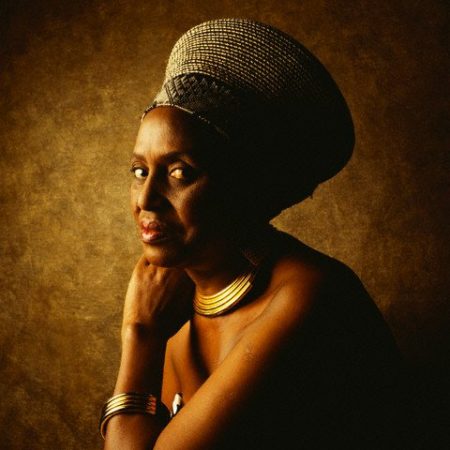

Miriam Makeba, nicknamed Mama Africa, African performer and civil rights activist

Miriam Makeba

Miriam Makeba, was born in 1932 in Prospect Township, near Johannesburg, South Africa. She would become known as Mama Africa, one of the world’s most prominent Black African performers and civil rights activists of the 20th century.

Makeba grew up in Sophiatown, a segregated Black township outside of Johannesburg, to a Swazi mother and a Xhosa father. She began singing in a school choir as a young girl. By the late 1950s, Makeba was a well-known recording artist and singer in South Africa.

After appearing in the documentary film Come Back, Africa in 1959, Makeba moved to the United States with the help of Harry Belafonte and other American performers. Makeba had a successful music career, including a Grammy award as well as introducing Western audiences to and popularizing Xhosa and Zulu songs.

She also became known for songs that publicly opposed the apartheid. In 1960, she was denied reentry into South Africa and lived in exile for the next 30 years.

In 1968, Makeba relocated with her husband to Guinea and then moved to Belgium, continuing to record and tour in Africa and Europe. In 1988, she published her autobiography Makeba: My Story. In 1990, Nelson Mandela encouraged Makeba to return to South Africa. In 1991, Makeba performed in South Africa for the first time since her exile.

She was internationally known for her songs “Pata Pata” and “Click Song” in English (“Qongqothwane” in Xhosa). Makeba made 30 original albums and 19 compilation albums. She was one of the first African musicians to receive worldwide recognition. Makeba brought African music to a Western audience and became a symbol of opposition to apartheid. When she passed away in 2008, Nelson Mandela said that “her music inspired a powerful sense of hope in all of us.”

“I have one thing in common with the emerging Black nations of Africa: we both have voices, and we are discovering what we can do with them.” – Miriam Makeba

Dolores Huerta, labor activist and leader of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement

Dolores Huerta. Image courtesy of the Chicago Tribune

Born in 1930 in New Mexico, Dolores Huerta was the middle child of Alicia and Juan Fernandez, a farm worker and miner (who later became a state legislator). Her parents divorced when she was only three years old, and Huerta moved to Stockton, California with her mother and siblings. Alicia’s activism in her community and acts of compassion towards workers greatly influenced Huerta as she grew up.

Huerta experienced repeated discrimination throughout her childhood. A schoolteacher accused Huerta of cheating because her papers were “too well-written” to come from a Mexican girl. In 1945, a group of white men brutally beat her brother for wearing a Zoot-Suit, a popular Latino fashion statement at the time.

In 1955, Huerta co-founded the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which led voter registration drives and fought for economic improvements for Hispanics. She also founded the Agricultural Workers Association. Huerta eventually met activist César Chávez, and in 1962 Huerta and Chávez founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), the predecessor of the United Farm Workers’ Union (UFW). Huerta served as vice president of UFW until 1999.

Despite facing both racial and gender discrimination, Huerta helped organize the 1965 Delano strike of 5,000 grape workers and led negotiations in the workers’ contract that followed. Over the years, Huerta organized workers, negotiated contracts, advocated for safer working conditions, including the elimination of harmful pesticides, and fought for unemployment and healthcare benefits for agricultural workers.

In 1973, Huerta led a consumer boycott of grapes that resulted in the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. For the next two decades, Huerta worked as a lobbyist to improve workers’ legislative representation. During the 1990s and 2000s, she worked to elect more Latinos and women to political office.

In 1998, Huerta received the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award. In 2012, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Dolores Huerta is one of the most influential labor activists of the last century and continues to be a leading voice and symbol for the Chicano civil rights movement.

“Every moment is an organizing opportunity, every person a potential activist, every minute a chance to change the world.” — Dolores Huerta

Catherine Booth, co-founder of the Salvation Army and influential preacher

Catherine Booth

Catherine Booth was born in 1829 in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, England, to Methodist parents. During her teenage years, Booth suffered from a spinal curvature and was forced to lay in bed months at a time. She spent most of her time reading, especially the writings of Charles Finney and John Wesley, and during this time not only devoted herself to the Christian faith but also felt a personal call to ministry.

In the early 1850s, she met and married a young preacher named William Booth. In 1859, Catherine Booth wrote Female Ministry: Woman’s Right to Preach the Gospel in defense of American preacher Mrs. Phoebe Palmer’s preaching, which had caused controversy amongst some Christian circles. Female Ministry advocated for women’s rights to preach and teach. In 1860, Booth preached for the first time herself during an evening service. Her reputation as an anointed and gifted preacher soon spread. She partnered with her husband in ministry and spoke to people in their homes, especially to alcoholics, whom she helped to make a new start in life.

Over the years, Booth became one of the most known and sought after communicators of her time. A woman preacher was a rare phenomenon in her day, and her magnetism and eloquence attracted large numbers to hear her messages, and she validated women’s place in ministry for many.

Catherine and William started The Christian Mission in 1865 (later known as The Salvation Army) in London’s East End. William preached to the poor, while Catherine spoke to the wealthy, gaining financial support for the ministry. Within 10 years, the organization had over 1,000 volunteers and evangelists. The Salvation Army preached the gospel first to robbers, prostitutes, gamblers, and drunkards.

Between 1881 and 1885, over 250,000 people converted to Christianity throughout the British Isles through their ministry. The Salvation Army spread rapidly to America and soon after to Canada, Australia, France, Switzerland, India, South Africa, Iceland, and Germany. Today, The Salvation Army is active in virtually every corner of the world and serves in 131 countries, offering the message of God’s healing and hope to all those in need.

“You are not here in the world for yourself. You have been sent here for others. The world is waiting for you!” — Catherine Booth

Madam C.J. Walker, the first Black woman millionaire in the United States

Madam C.J. Walker. Image courtesy of Getty Images

In 1867, Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove to her parents, Louisiana sharecroppers who had been born into slavery. Walker was the first in her family to be born free after the Emancipation Proclamation. Her childhood was filled with hardship. She was orphaned at 7 years old, married at 14, had a daughter, and became a widow by the time she was only 20 years old.

Walker then moved with her young daughter to St. Louis, where she worked as a laundress while attending night school. She joined the choir of the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and became active in the National Association of Colored Women. Also in St. Louis, she met Charles J. Walker, who would become her second husband.

After a scalp disorder caused her to lose much of her own hair, Walker created a hair care line for Black women that would revolutionize the Black hair care industry.

Known as the “Walker System,” her hair care involved scalp preparation, lotions, and iron combs. At a time when most other products for Black hair were largely manufactured by white businesses, she set her line of products apart by emphasizing the health benefits to her customers. She sold directly to Black women, and her personal touch created a loyal and growing fan base. As the business grew she employed sales women she called “Beauty Culturalists.”

Walker moved to Denver, Colorado, in 1905, with just $1.05 in savings in her pocket. By 1908, Walker opened a beauty school and factory in Pittsburgh named after her daughter. Two years later, she moved her business headquarters to Indianapolis, which provided access to railroads for distribution and a large population of Black customers. At the height of production, the Madam C.J. Walker Company employed over 3,000 people, mostly Black women who sold Walker’s products door-to-door.

Walker became one of the best-known African Americans of her time. Her business success allowed her to live much differently than her upbringing. Walker’s country home in Irvington-on-Hudson, was designed by Black architect Vertner Tandy. Her Manhattan townhouse became a salon for members of the Harlem Renaissance when her daughter inherited it in the 1920s.

Walker was quite the philanthropist, establishing clubs for her employees and encouraging them to give back to their communities with financial bonus incentives. Her generosity extended to educational causes and Black charities, funding scholarships for women at Tuskegee Institute and donating to the NAACP, the Black YMCA, and many others.

Madam C. J. Walker died at the age of 51. Her legacy inspired generations to pursue financial independence, business success, and philanthropy work.

“I got my start by giving myself a start.” –Madam C. J. Walker

Lois Jenson, the first person to file a class-action sexual harassment lawsuit in U.S. Federal Court

Lois Jenson. Image courtesy of mesabitribune.com

In 1974, nine of the United States’ largest steel companies signed a consent decree with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the Labor Department that required the industry’s mines to provide 20% of its new jobs to women and minorities. The following year, four women began employment for the first time at the Eveleth Mines Forbes Fairlane Plant in Northern Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range. Among them was Lois Jenson, a 27-year-old single mother. The job appealed to Jenson because it paid three times more than she was able to make elsewhere and provided health benefits for herself and her family.

Jenson’s male co-workers vocally opposed the hire of female employees, and her work environment grew increasingly hostile. Pornographic photos and graffiti began began appearing in the mines. Sex toys appeared in the women’s workspaces. Lewd jokes and unwelcome physical contact from co-workers and supervisors became the daily norm. As more women were hired, the behavior escalated into stalking, assault, and threats of rape.

When women complained, they were met with threats or forced to work in isolated parts of the plant. One woman was forced to work with a man who would drop his pants when they were alone. The women were not provided with adequate bathroom facilities on site. Many women stopped drinking and held their urine for hours, resulting in extreme dehydration and severe bladder and kidney infections.

In 1984, Jenson was stalked by a coworker who broke into her home and threatened her son. The union refused to help and management never transferred the coworker. Jenson then filed a complaint with the State Department of Human Rights. The State requested that the mine institute a sexual harassment policy and pay punitive damages for mental anguish. The company agreed to adopt a sexual harassment policy but refused to make any financial restitution. During this time the ongoing harassment intensified. The case dragged on for the next several years with no progress until an attorney from the Attorney General’s Office convinced Jenson to turn her complaint into a class action lawsuit. From there she hired a private law firm. After unsuccessfully trying to persuade other women to join her, she finally found support in her friend and coworker, Patricia Kosmach. Together, they convinced others to join them. In 1988, the lawsuit was certified as a class action with the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota.

The plaintiffs, including Jenson, were willing to settle the case, but Oglebay Norton (owners of Eveleth Mines) refused and the case continued for 10 more years. Finally in 1992, they went to trial and the court ruled against Oglebay Norton.

Jenson’s courage was groundbreaking. The lawsuit made history because it was the first to address sexual harassment as a systemic problem and established that corporations are responsible for ensuring harassment-free work environments.

“This was about sexual harassment and being able to go to work knowing you were going to come home safely, but also that you could go to work knowing that you would not be grabbed or raped, or have these verbal abuses.” –Lois Jenson

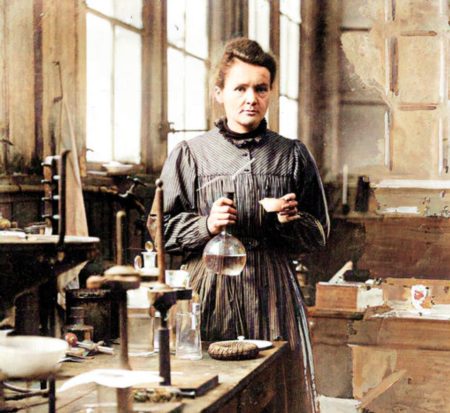

Marie Curie, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the only woman to win the award in two different fields

Marie Curie. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Marie Curie was born in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland. From early childhood, Curie had a remarkable memory and at 16 years old she won a gold medal when completing her secondary education. When her father lost his savings after a bad investment, Curie began working as a teacher while also participating in the nationalist free university, reading Polish to women workers. At 18, she became governess and used her earnings to finance her sister’s medical studies.

In 1891, Curie went to Paris and began to follow the lectures of Paul Appell, Gabriel Lippmann, and Edmond Bouty. She met well-known physicists Jean Perrin, Charles Maurain, and Aimé Cotton. In 1893, she received her license of physical sciences and soon after began to work in Lippmann’s research laboratory. The following year, she was placed second in the license of mathematical sciences and also met her future husband, Pierre Curie.

Their marriage proved to be a dynamic partnership. Together they discovered polonium and then radium a few months later. While Pierre devoted his experiments to the physical study of these radiations, Marie worked to obtain pure radium in the metallic state with the help of the chemist André-Louis Debierne. After achieving her goals and documenting her findings, Marie Curie received her doctorate of science and, alongside Pierre, was awarded the Davy Medal of the Royal Society. In 1903, the Curies, along with Henri Becquerel, won the Nobel Prize for Physics for the discovery of radioactivity.

After Pierre’s sudden death in 1906, Marie devoted her energy to completing the scientific work they had begun together. That same year she became the first woman to teach in the Sorbonne. Two years later, she became titular professor.

Her fundamental treatise on radioactivity was published in 1910, and in 1911 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, for the isolation of pure radium.

During World War I, Marie Curie, and her daughter Irène, worked on the development of X-radiography. Curie became a member of the Academy of Medicine in 1922 and focused her research on the study of the chemistry of radioactive substances and the medical applications of these substances.

In the 1920s, Curie gave lectures in many countries. She was made a member of the International Commission on Intellectual Co-operation by the Council of the League of Nations. In 1932, she saw the opening of the Curie Foundation in Paris.

In 1934, Curie died as a result of aplastic anemia caused by radiation. In 1995, her ashes were enshrined in the Panthéon in Paris, the first woman to receive this honor for her own achievements.

“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.” –Marie Curie

Related Resources

6 Female Thought Leaders to Follow

Finding new role models isn’t easy. With unlimited access to millions of creators, entrepreneurs and businesses online, it can be hard to narrow it down to who’s really trustworthy and worth following. In this article we partnered with cred, a specialized...

How I Found My Voice and a Company That Values My Talent

One of the happiest days of my collegiate experience was a random day during my first semester of freshman year. My advisor had communicated to me that if I played my cards correctly, I could graduate at least a semester early. I was ecstatic to know my hard work...

AAPI Women Who Inspire Us: Becky Wu

One of my favorite things to do as a writer is gush about women who inspire me. It’s important to remind ourselves that there are female agents of grace and change in our world working under the radar to lift others up. As an actor, I’m grateful to know women in the...